#16 – The Making of D.A.M.N.*

A behind-the-scenes look at one of the most useless LLM ever trained.

In May 2025, during an involuntary hiatus from commercial work, our Research and Development department (i.e., anyone willing to give in on a quiet day) decided to revive a dormant idea. We opened a folder of forgotten text files labeled future projects and scrolled attentively through fragments written in better times. Among them, one idea stood out: building hardware. It seemed the most challenging, and therefore the most captivating.

Our modest funding demanded that ambition correspond with simplicity. Perhaps a microcontroller, maybe a small LCD screen, and a trigger to activate it. What began as a sketch on a napkin soon spiraled into a storm of experiments and speculative thoughts. What purpose could such a device have, other than occupying de-clientelized studio time with research and daydreams? Was simplicity a question of hardware, or of material desire? And if simplicity can be achieved through matter, could its function become a fake feature—a decoy? A trick?

At first, we thought the device might display the studio timecode—the very time we were investing in building it. It felt right, perhaps too right, too flat. But it pointed in an interesting direction: maybe a machine didn’t need to be useful at all. This inversion—questioning purposelessness as a valid function—shifted the entire project. Why not build a device that exists for its own sake, like Munari’s whimsical machines or Mizscky’s contraptions?

In 1937, Bruno Munari described his useless machines in La Lettura:

“Useless because they do not manufacture, do not eliminate manpower, do not save time or money, do not produce anything marketable. They are nothing more than colored mobile objects, specially designed to achieve that particular variety of combinations, movements, shapes, and colors. Objects to be looked at as one looks at a shifting mass of clouds after having spent seven hours inside a workshop full of useful machines… A useless machine that represents absolutely nothing is the ideal device thanks to which we can calmly revive our imagination, daily afflicted by useful machines.”

Munari’s useless machines were, paradoxically, very useful—for critique, for imagination, for repair. In a time when cloud-spotting has become a dream and our eyes are glued to algorithmic feeds of meaningless forms, we thought: what if language itself became the material of a useless machine?

So we turned to stochastic nonsense. To simple perturbations, Markov chains: predictive language models.

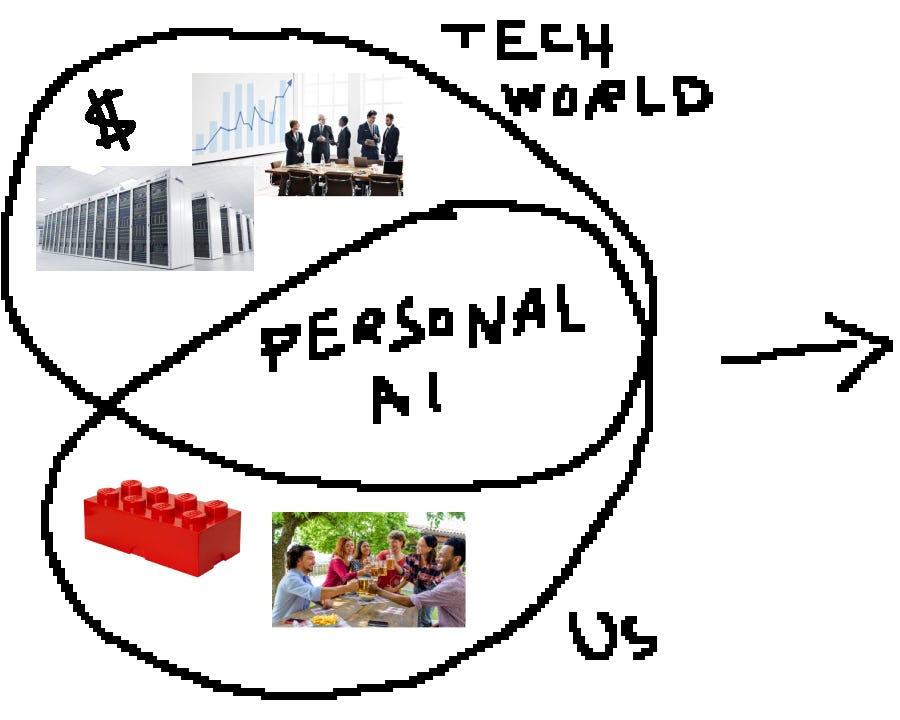

But what does it actually mean to build a large language model? Training requires staggering resources—GPU clusters, vast datasets, huge amounts of electricity, and water to keep the systems cool. By 2025, rumors claimed training costs for closed-source models had reached half a billion dollars. For almost everyone, this scale was unthinkable.

Then we discovered this repo by DaveBben that cracked our assumptions: a compact language model running on an ESP32, a microcontroller with barely 4 MB of RAM. The very idea that such a tiny device could host something reminiscent of ChatGPT was both absurd and exhilarating. We are used to associating language models with data centers and planetary-scale computation. Yet here was a toy-sized board muttering its own little thoughts.

The ESP32 experiment revealed that if we could shrink the problem space, we could shrink the model itself. A Little Language Model—a LLM of another kind—might fit in a few megabytes and be trained in hours.

Of course, specialization comes with limits. A small model has narrow knowledge, poor coherence, repetitive syntax. It speaks badly. But instead of treating this as a flaw, we saw it as a voice. The broken language could define the machine’s character: Brainrot itself. Language at its core uselessness.

The broken model matched the broken world.

We scraped a dataset of Italian Brainrot—sentences, memes, characters—then trained a miniature model using a pared-down LLaMA 2 architecture. Implementation was, predictably, difficult. Overfitting made it recite the dataset by memory. Limited variety made it repeat the same figures endlessly. And because Brainrot itself is structurally damaged, the model struggled to learn at all.

A screen recording of the terminal window showing text generation of an early model version.

To counter this, we pre-trained on simple Italian sentences before fine-tuning on Brainrot, and used Markov-generated “creatures” to enrich the corpus. This hybridization worked unexpectedly well. The model began to speak: badly, haltingly, vulgar.

An early experiment with Markov chain trained on a song by a famous Milanese rap band from the 2000s.

At this stage, the prototype ran on an ESP32 WROVER with a small OLED display. The next question was how to power it. Early ideas included a hand crank or even a hydroelectric turbine attached to a sink—solutions that were clever but felt theatrical, too bound to human muscle and infrastructure. We wanted the device to live by its own rhythm, to draw from the same source that has fed every new organism, every new circuit, every photosynthetic process since the beginning: sunlight. To let the machine depend on it was to acknowledge a common condition. In this sense, the act of raising the device toward the sun was not symbolic but ontological—a small ritual of dependency, aligning the machine’s metabolism with that of the planet.

We assembled the system on a breadboard, wired the panels, borrowed a multimeter from a nearby repair shop, and began debugging. Hours passed re-soldering connections, balancing voltage, and stabilizing the boot process with capacitors. At last, the machine ran under sunlight. It was simple, not minimal; not merely a piece of iron, but something alive enough to misbehave.

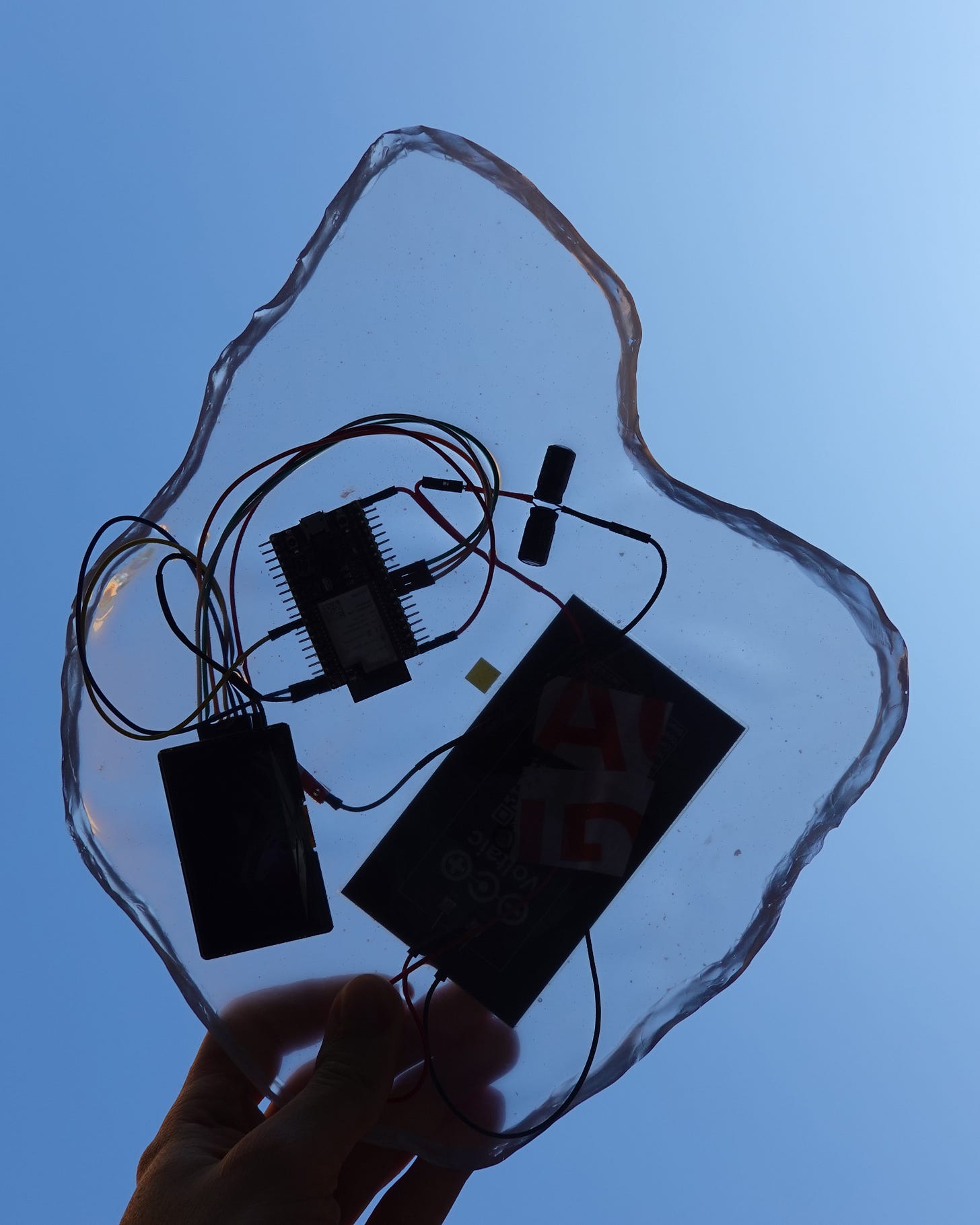

The final challenge was form. We wanted it handheld, yet the usual plastic casings felt too sterile. Then we found an image of a Raspberry Pi encapsulated entirely in translucent resin—suspended like a fossil in amber. It clicked immediately. The resin would not just protect the device; it would preserve the electronics as if they were relics of an extinct computation. The machine became a vessel of trapped language, a fossil of contemporary signal processing.

The metaphor deepened. Amber preserves DNA; resin preserves data. Jurassic Park revived dinosaurs from fossilized code. Our device, likewise, carried the strange, decaying language of the present into an imagined future—an archaeological relic of now.

By coincidence, a new film in the saga, Jurassic World: Rebirth, was about to be released. It felt like the world was repeating itself, training on its own dataset.

And so the useless machine came to life: D.A.M.N - Demented Apparatus For Model Necrosis. A solar-powered, resin-encased, Italian-brainrotted, little-language-fossil.

A machine that does not predict, does not optimize, does not monetize.

It only hallucinates under the sun.

You can read more about D.A.M.N and its digital discombobulations on this website.

Hope you enjoyed :)

If you want to learn more about upcoming projects from Giga you can also follow us on Instagram and check our website.